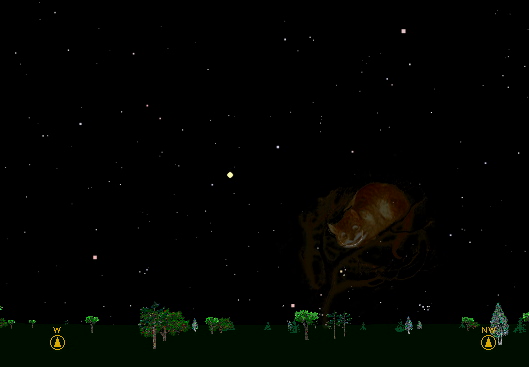

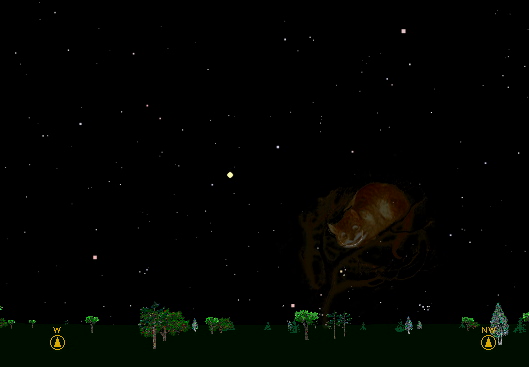

Oxford, England : Looking west-northwest at 9 p.m., 4 May, 1859.

![]()

My name is Hans Havermann and I am a fan of Lewis Carroll. The Cheshire Cat figures prominently in chapter VI of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: Pig and Pepper. On (or about) 1 June 1984, I found myself gazing up at the big umbrella of a maple tree in my back-yard when I spotted, in the fork of a branch, what I took to be some sort of cosmic joke. All I could do was smile back. It was the two-day-old 'waxing crescent' of lunation no. 760 (there had been a solar eclipse on 30 May), barely visible in the mid-afternoon with the sun still well above the horizon. I ran inside the house to re-read 'Pig and Pepper' in Martin Gardner's 'The Annotated Alice'. The more I read, the more it made sense to me that the Cheshire Cat might have been a deliberate Carrollian metaphor for the moon. I wrote Gardner about it and he acknowledged (6 August) some originality to the connection. Not that the association was entirely unthought of. The Disney Cheshire Cat, for instance, materializes out of a risen moon. Where I differed, perhaps, was in my belief that the connection was intentional and not mere happenstance. However, I couldn't come up with a convincing argument for a possible Carrollian source of inspiration. I had asked Guy Ottewell (author of the yearly 'Astronomical Calendar') for a phase-of-the-moon calculation for 4 July 1862, the date of the "golden afternoon" that prefaces Alice's Adventures. His (27 August) response was that "when it rose about noon it might have been just a little noticably smile-shaped (though tilted far backward when rising)". Not too encouraging. At any rate, records for Oxford, on that date, supposedly indicated the weather to be "cool and rather wet".

Six years later, Martin Gardner published his 'More Annotated Alice'. I rated a mention. On 12 May 1990, the Lewis Carroll Society of North America held its first ever meeting outside of the United States... in Toronto. I was pleased to be able to attend. Joe Brabant gave a speech entitled "Wouldn't It Be Murder?" wherein he made mention of the fact that Wonderland takes place on Alice Liddell's seventh birthday. Of course! Gardner's annotations had deduced the conjecture, but I missed it. I wrote another letter to Ottewell but received no reply. However, knowing that Alice's birthday that year came ten days after Easter convinced me I was close.

What was Lewis Carroll doing on (or about) 4 May 1859? Alas, his diaries for 18 April 1858 to 8 May 1862 are missing. The closest I have been able to get is a letter dated one week after the birthday (in Morton N. Cohen's 'The Letters of Lewis Carroll'), wherein Carroll talks of meeting a Mr. Warburton (brother of a then-popular 'Eastern Travel' book called "The Crescent and the Cross"):

"It was a fine moonlight night, and he walked through the garden with me when I left, and pointed out an effect of the moon shining through thin white cloud which I had never noticed before - a sort of golden ring, not close round its edge like a halo, but at some distance off. I believe sailors consider it a sign of bad weather. He said he had often noticed it, and had alluded to it in one of his early poems: you will find it in 'Margaret'."

The first stanza of Margaret reads:

The very smile before you speak That dimples your transparent cheek Encircles all the heart, and feedth The senses with a still delight Of dainty sorrow without sound, Like the tender amber round Which the moon about her spreadeth Moving thro' a fleecy night.I'm not sure this smile is the same one T.S. Eliot had in mind when he concluded 'Morning at the Window' with:

An aimless smile that hovers in the air And vanishes along the level of the roofs.We may never know if Carroll actually witnessed the sky on the night in question. My picture is a simple composite of a Macintosh 'Starry Night' simulation and a reworking of the famous John Tenniel drawing of Alice gazing up at the Cheshire Cat out of 'The Nursery Alice'. The most difficult part was (manually) resizing and rotating the Cat so that its 'grin' would coincide with the lunar crescent. It is about an hour and a half after sunset and an hour and a half before moonset. The bright star in the lower left of the picture is Betelgeuse; the one in the upper right, Capella. The brilliant object between them is not a star, but the planet Jupiter. Underneath the left horn of the lunar crescent is Mars, flanked by two Tau stars. Near the horizon, on Mars' left is Aldebaran, and on Mars' right, the Pleiades or Seven Sisters.

Lunar folklore likely predates the classical mythology of Artemis/Diana, in all her variant forms. Most of it is superstition, but there are hints of prescientific thinking. The moon, after all, is as good a symbol as any of the conundrum posed by the concept of action-at-a-distance.

Our 'week' is an artificial construct based on an attempt to squeeze the lunar month into four equal parts. The days of each part were to be coupled with the then-known seven wandering gods. Dies Solis is the Sun's day; Dies Lunae, the Moon's day; Dies Martis is the Saxon Tiw's day; Dies Mercurii, Woden's day; Dies Jovis, Thor's day; Dies Veneris, Frigg's day; and Dies Saturni, Saterne's day. How they came to be in this order is an interesting question.

The connection of 'seven' with the rhythms and cycles of life have been reinforced by occultists through the ages: the human body, for instance, was believed to renew itself every 7 years. With the moon's phases providing a powerful visualization tool for the concept of cyclical change (death and rebirth), perhaps it is fitting that the illustrated night sky appeared as it did for Alice Liddell's seventh birthday.

![]()

13 April 2008 © Rarebit Dreams